Evidence of Potential Outcomes or Longer-Term Effects

Experiencing incidents of hate can cause trauma. The impact of trauma can also manifest in various forms of behavior and mood changes.

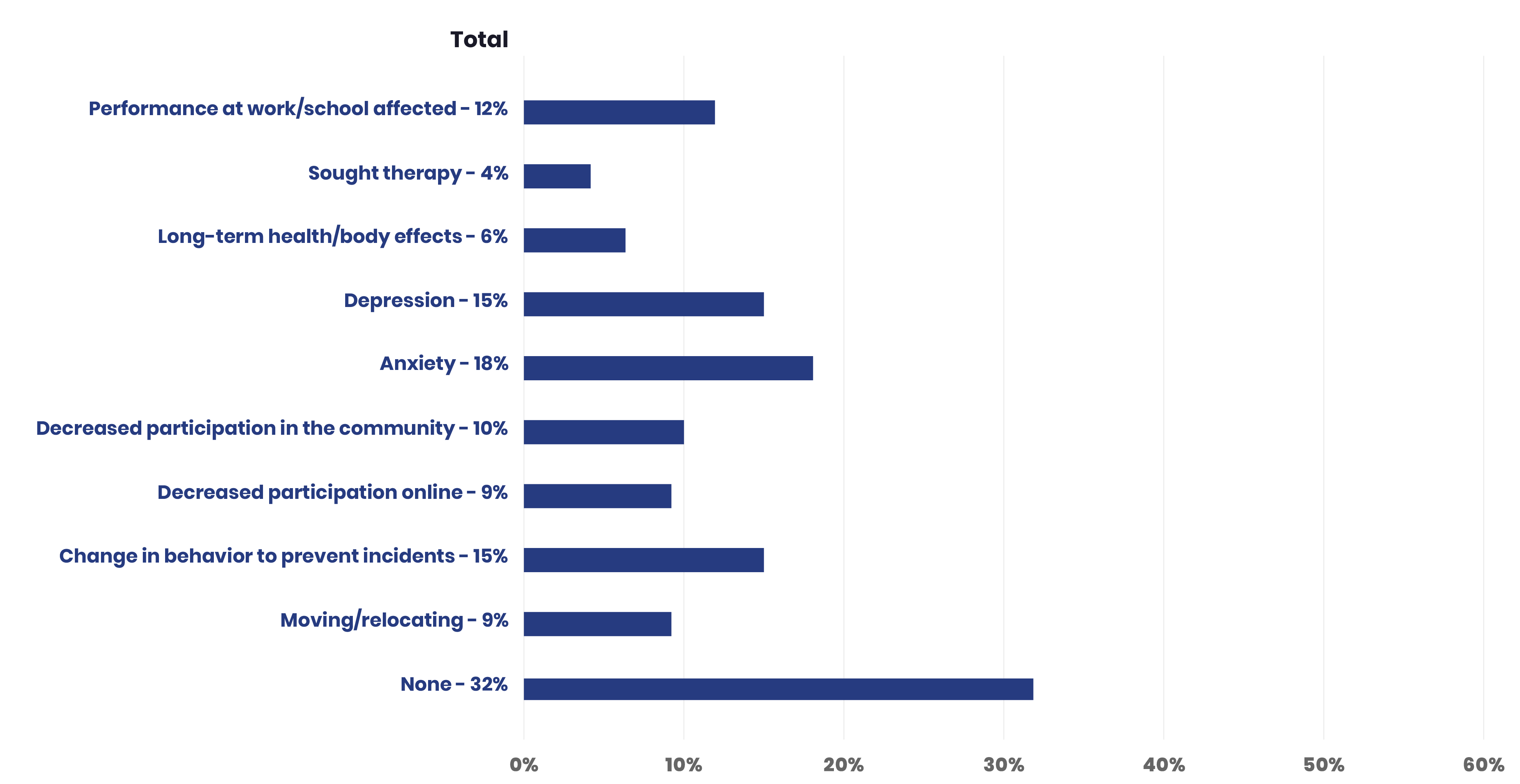

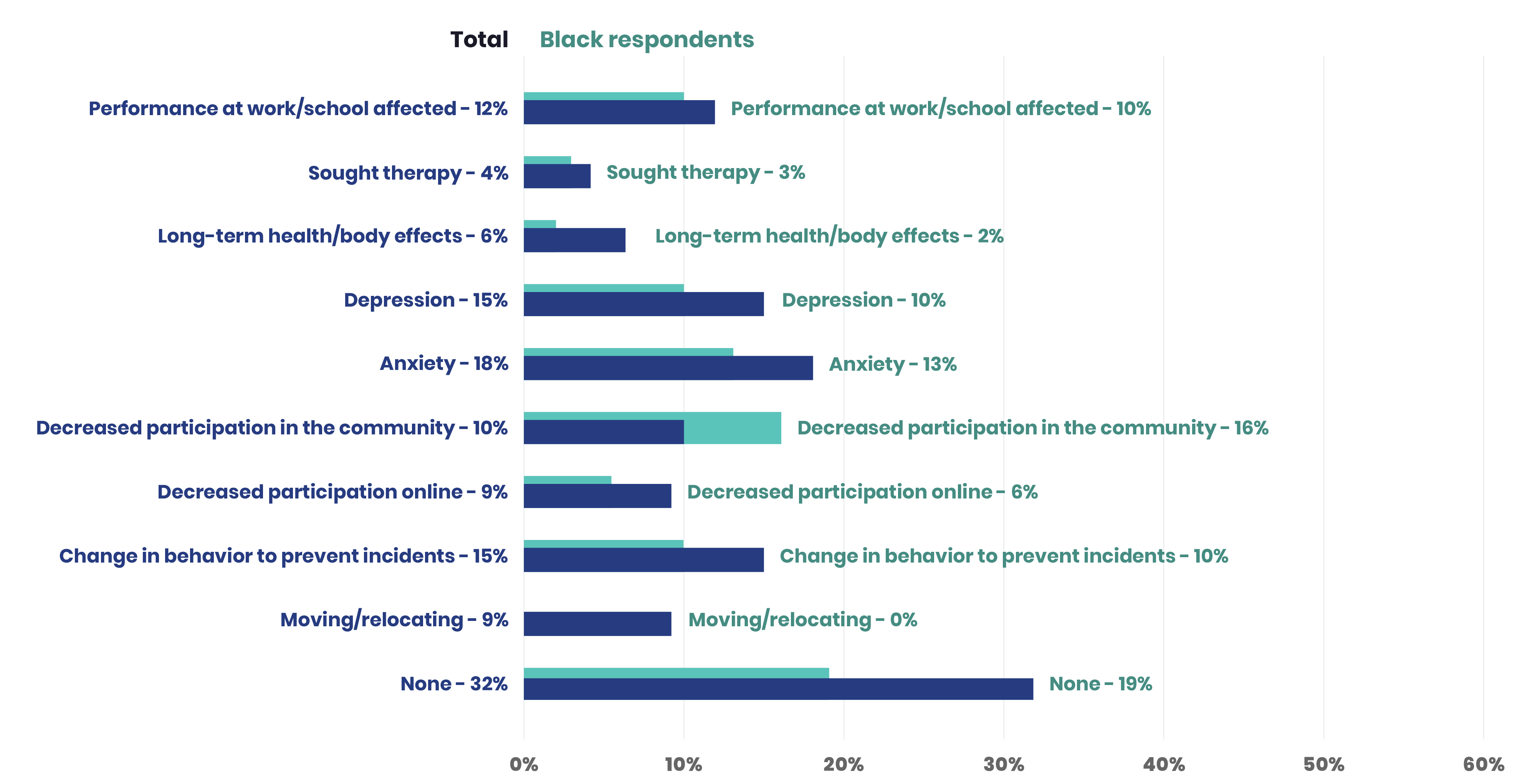

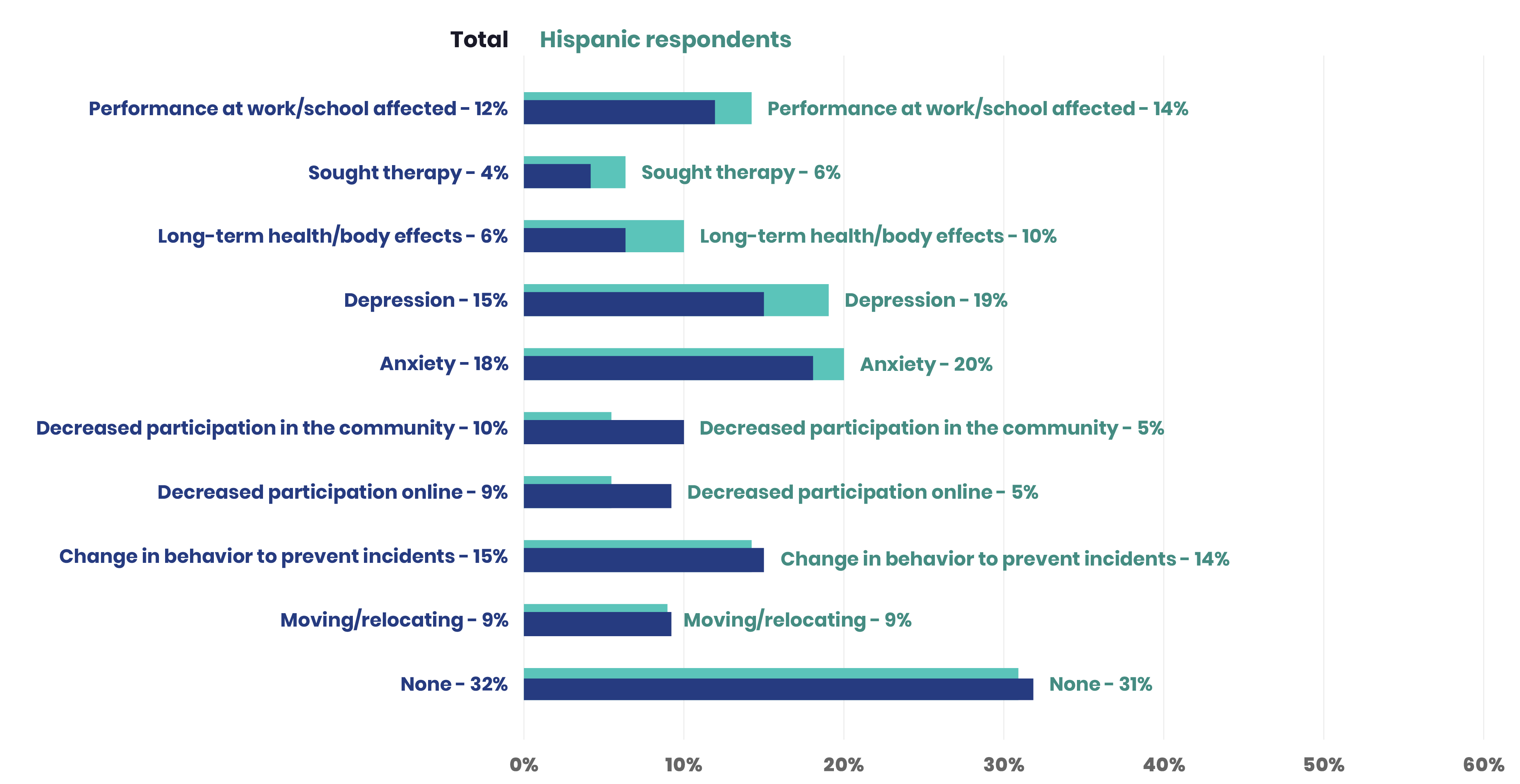

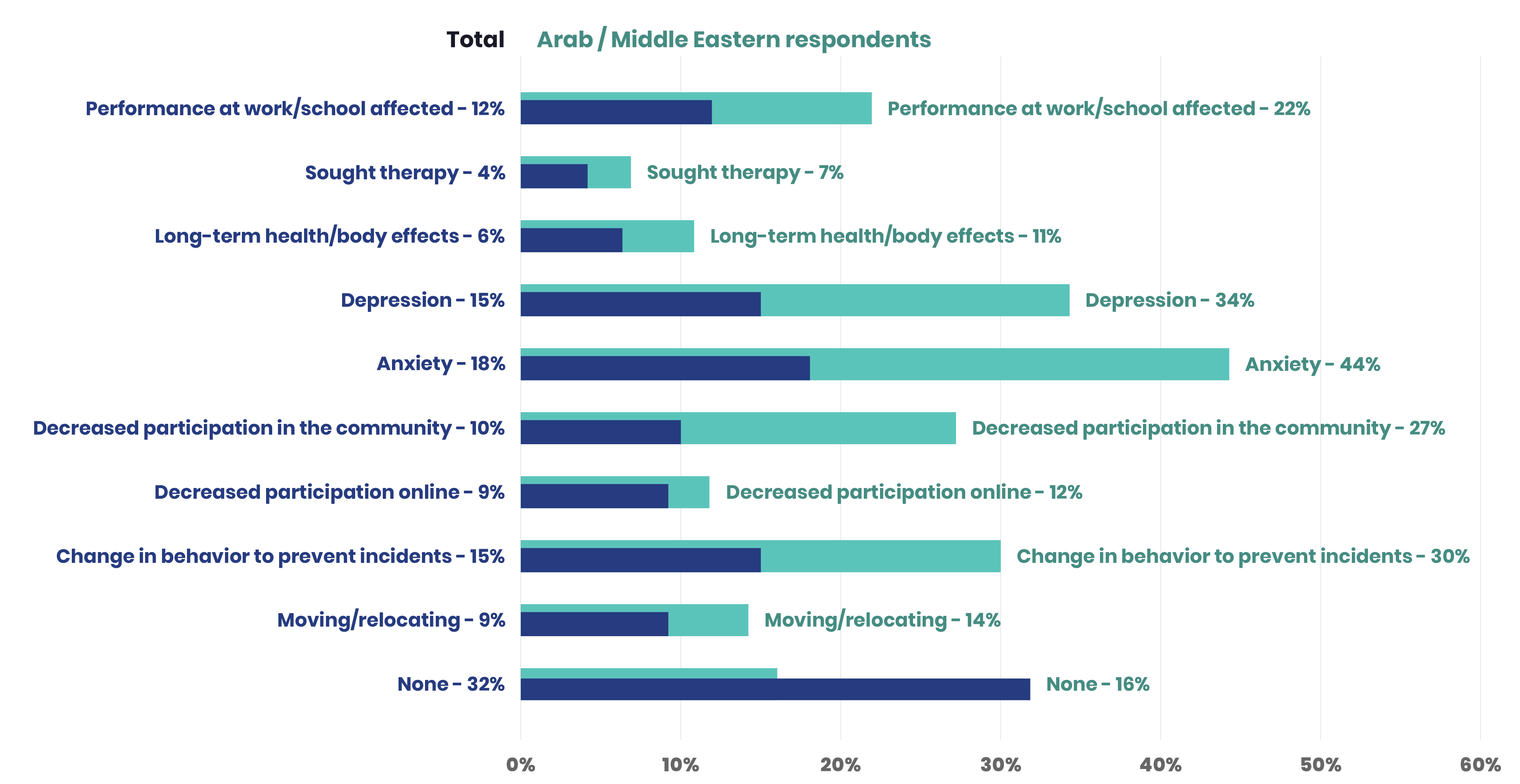

Some incidents in the CAH database note that the impacted individual experiences a change in behavior and/or participation, a deterioration of their emotional and/or physical health, and a change in their performance at work or school. The database shows changes in behavior because the hate incidents tend to cluster around several courses of action including increasing security (purchasing security cameras, fences, extra locks, or motion-sensor light) around respondents’ homes, preventing children from playing outside, being more aware or fearful of one’s surroundings when out on the street, changing one’s actions while outside, or relocating. In the Hate Incidence Poll, 15 percent confirmed that some experience a desire to change behavior to prevent future incidents. An example of this behavior appears in the CAH database. A report to the CAH database reads that a woman who owns a salon received repeated threatening, racist letters as well as vandalism to her business. She reinforced the security of the premises, stating “Those locks are on that door because I'm scared. I am. I don't know what is going to happen next.” Additionally, some parents in the CAH database whose homes have been impacted prevent their children from playing outside. An individual reported that their neighbor repeatedly threatened them with a pellet gun or hurled racist slurs. The parents grew afraid of what the neighbor might do and said, “They were afraid to allow their sons to play in the yard, and [the father] felt helpless to protect them.”

Some individuals in the CAH database change their actions while outside, which involves no longer wearing certain religious items, listening to music, only speaking English instead of a native language, or no longer wanting to show affection to a partner. An individual reported, “Students have called me ‘ch***’ several times while walking past them. I've also had a student spit on my feet. Consequently, I listen to music every time I'm walking to and from work.” In another individual report, the daughter of the reporter’s friend was repeatedly harassed by children at school who shouted, “Build that Wall” and told her that she would be deported. The reporter stated, “These types of incidents have continued to happen and my friend's daughter is so afraid of the comments, that she's asked her mother to only speak English when they are out together.”

In another CAH incident, an interracial couple was harassed by a man who didn’t think that a White woman and a Black man should be together. When they showed affection towards each other, the man told them to stop. The couple brushed the incident off; however, the woman stated, “I'm still a little afraid to show public affection to my partner because of this incident.”

Some individuals in the CAH database decide to relocate from the neighborhood where they experience hate. An individual reported, “[an] African American pastor was spit on and harassed to the point she left town out of fear for safety.” These changes tend to occur most commonly after repeated harassment or multiple hate incidents from the same source, although single, severe incidents can still trigger these effects. In the Hate Incidence Poll, 9 percent of individuals also reported wanting to move or relocate following an incident.

Changes in participation, on the other hand, tend to occur after a single incident in the CAH database (e.g., an Uber driver being reluctant to ever drive again after facing a verbal assault from a passenger; churchgoers staying home from church after vandalism; a couple leaving town after their property was spray-painted with abusive language; a person deleting a comment in support of a political candidate after written abusive language). Experiencing repeated harassment often leads to people not wanting to leave their home, according to several instances in the CAH database (e.g. “she was utterly traumatized and no longer wants to leave the house by herself, as a black-haired, olive-skinned Muslim woman,” “Due to the stress and fear, I really don’t leave the house”). In the poll, 10 percent stated that they changed their participation in their community and 9 percent stated that they changed their participation online.

Noted effects in the CAH database of a hate incident on a respondent’s physical health range from concussions to stab wounds to broken bones, to even more serious injuries that require major surgeries such as facial reconstruction, amputations, or removal of an eye. For example, a man and his friend were attacked and called a gay slur. After the attack, he was told by doctors that he may lose sight in his left eye. In the poll, 6 percent of respondents stated that they experienced long term health or body effects following an incident.

Effects on emotional health often center around fear. In the CAH database, “A local woman said she's now scared just to walk down the street after being violently attacked in [a city] for being gay.” In another example, an individual with her friends was eating ice cream when the group was attacked by another patron who verbally abused them until they ran away. The woman stated that following the incident, “If I feel like anyone looks at me in a strange way I get scared that they will jump at me, try to rip my hijab off, or yell discriminatory, racist expletives my way.” In several cases the two are linked, with respondents’ emotional health suffering after a physical attack. The Hate Incidence Poll discovered that depression and anxiety among impacted individuals were represented at 18 percent and 15 percent of the respondents respectively.

The CAH database shows performance at work or school is affected either because the incident occurs at their school or place of work or because the individual is impacted by an incident that happened elsewhere. In the Hate Incidence Poll, 12 percent of individuals report that their performance at work and/or school is affected. Respondents miss work due to physical and emotional health consequences from hate incidents. For example, an individual was attacked and called homophobic slurs. The physical ramifications of the attack “has rendered him unable to work for the next month.”